By KJ Naum

As the Mississippi River flows from its source in northern Minnesota to its mouth on the Louisiana coast, its waters cross the boundaries of ten states, picking up a lot along the way. This includes nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous, which contribute to “dead zones” where the river drains into the Gulf of Mexico. Dead zones occur when too much nutrient pollution causes algae to grow excessively. When they die, the decaying cells consume oxygen, depriving other life forms of the oxygen they need to survive. This condition, known as hypoxia, can lead to the devastation of entire ecosystems if left unchecked.

There’s not a lot of mystery about what causes nutrient pollution. Widespread agricultural practices in the Midwest’s Corn Belt encourage the plentiful use of nutrient-based fertilizer, so much so that much of it washes away even before the crops can use it. But trying to understand how it’s happening remains a challenge. The data on the river is as free-flowing as the water itself—and often just as slippery.

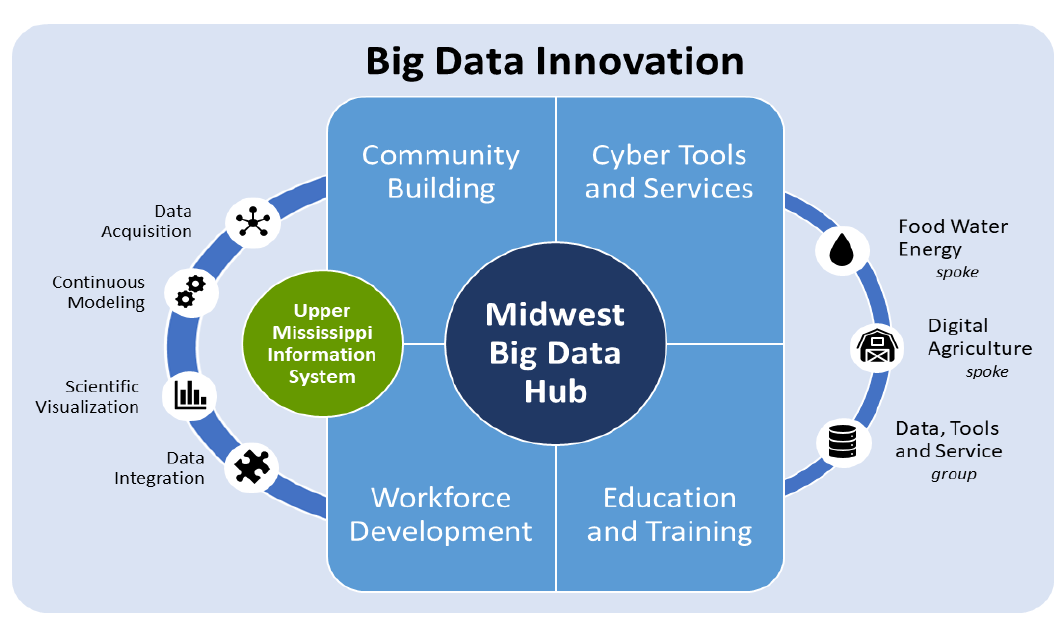

“Lots of people are doing water quality monitoring, and there are maybe hundreds or thousands of water quality parameters that can be tracked,” says Chris Jones. Jones is a research engineer at the University of Iowa, who works with the Upper Mississippi Information System (UMIS), an online platform that aims to make this deluge of data more accessible and manageable. Jones also works on the Iowa Water Quality Information System (IWQIS), an ongoing effort that informs this newer project. IWQIS makes real-time water quality data from within the state of Iowa available to researchers and the general public. However, the UMIS team is thinking bigger than that. Jones notes, “Watershed boundaries are different from political boundaries. We have to think within their context if we’re going to improve water quality, and so our vision was to bring the IWQIS concept to a larger geographical area.” The Upper Mississippi Information System aims to do exactly that. A team of researchers at the University of Iowa, Iowa State University, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are working together on building the UMIS platform and wrangling the data for public consumption. The online platform provides one-stop access to independently managed data streams—both real-time and historical.

The initial site is live, and Jones characterizes it as about halfway complete. The biggest task for the team is to acquire still more data through building partnerships with other organizations. “We’re mainly focused on nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus right now, but some other data will likely be available,” Jones says. “We had to start somewhere. This is a good place to start because it’s what many people are most interested in.”

Despite the widespread interest, combating nutrient pollution in the Midwest is an uphill battle. Unlike other U.S. water systems like the Chesapeake Bay, the states of the Mississippi basin have chosen not to regulate nutrient reduction, thanks to a powerful agricultural lobby that is opposed to such mandates. Instead, the state governments each try to promote and incentivize more widespread adoption of practices that reduce nutrient flow.

Jones, however, is skeptical that meaningful change can happen without collaboration. “The states will have to work in concert in order to have any meaningful impact on solving hypoxia,” he says. “That means giving scientists access to a lot of data. Having access to sound scientific data is critical for making policy.”

Individuals and organizations that are interested in the UMIS project can sign up to be a data partner or beta user via the UMIS website, or contact the team via email. Jones and the team are hopeful that UMIS will help drive change at the scale that is needed. “Nutrient pollution is one of the wicked problems, along with climate change, but we know there are solutions out there,” he says. “Solving this is a sociological and economic issue. Hopefully, UMIS can be a tool for policymakers to do just that.”

Get involved

Contact the Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub to suggest other projects we should highlight on this blog, or to participate in any of our community-led Priority Areas.

The Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub is an NSF-funded partnership of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Indiana University, Iowa State University, the University of Michigan, the University of Minnesota, and the University of North Dakota, and is focused on developing data science collaborations in the 12-state Midwest region. Learn more about the NSF Big Data Innovation Hubs community.