By Ken Ogata

From smartphones to surveillance cameras, to automatic doors and artificial intelligence, the cities we live in have become “smarter,” carrying the promise of productivity and modernization. While “smart” technology seemingly makes our lives easier, are we giving up the benefits of privacy and individualism?

In a new book, Governing Smart Cities as Knowledge Commons, edited by Brett M. Frischmann, Michael J. Madison, and Madelyn Rose Sanfilippo, experts in law, policy, and information science examine how we can properly govern “smart” cities through models based on ethical and social considerations, and information science.

With the increasing integration of technology into our daily lives, the amount of data and information that is gathered, stored, and analyzed by cities has skyrocketed.

“Residents are connected to each other and to governments and other organizations by fiber and wireless connections.” The authors of Governing Smart Cities as Knowledge Commons write in Part 1 of the book, “‘The people’ and their environments are rendered and represented digitally in the bureaucracies of public administration and in the dynamics of everyday life.”

As the role of Big Data becomes more important in city policy, data governance—the standards and regulation for the storage, usage, and disposal of data—has never been more relevant. Dr. Angie Raymond, who coauthored a chapter in the book and is a Professor of Business Law and Ethics at Indiana University, states that many cities in the United States lack the manpower and expertise to efficiently use the data collected.

“The problem a lot of cities are facing is that the skills required to use data are new,” Raymond said. “And unfortunately, cities are oftentimes well behind the curve on being able to find (well-trained) employees.”

Raymond added that many cities lack the infrastructure to store data for proper use later down the road. “The biggest issue for cities is oftentimes cities have been gathering data for a long time . . . they have a repository of data, which is oftentimes a Box folder with some security on it, and a lot of PDFs, which are incredibly difficult to be used.”

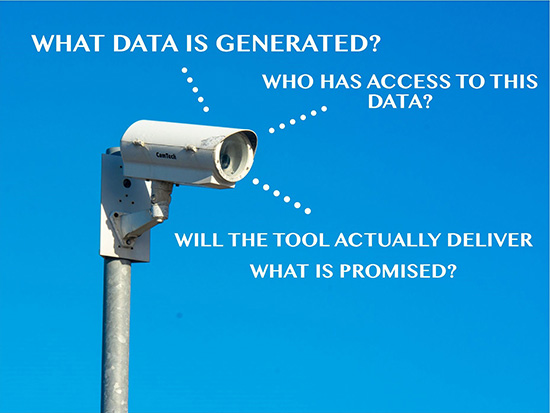

The authors also state that modern cities can get wrapped up in hype and adopt “smart” technology for the sake of modernization, not taking the time to consider what data it shares and collects and how to properly govern it.

The book notes that seemingly innocent examples of “smart” technology can have unintended consequences, such as an automatic door with a camera.

“What if the automatic door could identify people prior to opening the door? What if the automatic door could send an alert when an unauthorized person attempts to enter the building?” the authors ask in Part 4: Lessons for Smart Cities. “This requires new sensors, intelligence-generating tools and processes (identification), and automated actions . . . The camera-based system collects much more data than is needed, creating privacy risks that are easily overlooked or underestimated.”

To prevent cases like this, the authors of the book present the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework as a useful tool when evaluating the governance of smart technology. The book emphasizes the importance of comprehensive public knowledge in regard to data storage and collection, and the implementation of new smart technology across the city.

“We need to figure out a way that we can all use data to produce information, and then we’re sharing it amongst a larger community,” Raymond said. “Commons is just a fancy word for saying we all get together and we know the boundaries and have a set of rules.”

As an example of the GKC framework, Raymond brings up the Dewey Decimal system present in libraries across the country and how it could be used to set up a proper data governance topology for cities.

“It doesn’t matter what library you walk into, if you walk to the fiction section, you can find Stephen King, and (000) is the computer science section in every library all round the world,” said Raymond. “If we could ever develop an actual system where we were using similar variables with similar labels (for city data), we would be in a different place.”

Using the GKC framework as a foundation, the authors of the book provide a set of questions that can be used by administrative governments when considering the pros and cons of installing smart technology:

In the book’s concluding chapters, the authors mention in Part 4 that proper data governance requires comprehensive public knowledge and also community members that are well informed and capable of taking action and voicing concerns about data collections and city projects. “Simply put, cities aren’t smart, but the people living and working in cities might be.”

In making sure that data governance is upheld and smart technology does not infringe upon the rights of citizens, Raymond urges those capable to make sure that their voices are heard. “Citizens need to understand that if you are in the room and you have a voice, there are probably three people not in the room who don’t have a voice.”

Cities themselves can only be as smart as the people living in them. Accountability lies not only in the hands of the experts, but also the larger city community, whose job it is to make sure that we still have a voice in our cities.

Get Involved

Those interested in the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) framework can access the official Workshop on Knowledge Commons Website for further explanations of the framework and future projects and events.

Contact the Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub if you’re aware of other people or projects we should profile here, or to participate in any of our community-led Priority Areas. The MBDH has a variety of ways to get involved with our community and activities. The Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub is an NSF-funded partnership of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Indiana University, Iowa State University, the University of Michigan, the University of Minnesota, and the University of North Dakota, and is focused on developing collaborations in the 12-state Midwest region. Learn more about the national NSF Big Data Hubs community.