By Qining Wang

Despite being a fundamental process for innovations in chemistry, biology, pharmaceuticals, materials science, etc., molecular discovery can be a time-consuming and labor-intensive endeavor. The traditional trial-and-error approach through experimentation does not always yield promising results. According to a Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) Registry analysis, scientists predict the number of stable light- and moderate-weight organic molecules to be more than 10180. Among those, only 1020 to 1060 are biologically relevant. That’s a lot of molecules, to say the least, let alone discovering the ones that we can use. In the meantime, hundreds of years of research hunting for molecules has yielded an array of successes and failures that we can harvest for data-driven molecule discovery.

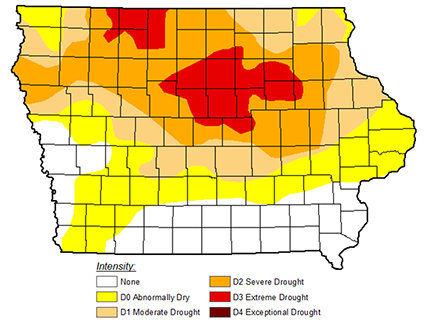

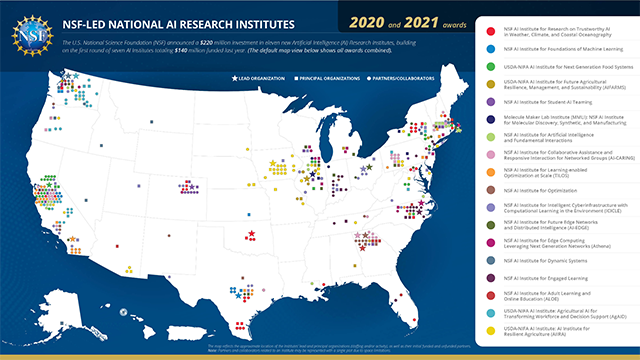

To that end, the Molecule Maker Lab Institute (MMLI) and many other AI Institutes funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (highlighted in the map below) decided to take this data-driven approach to find the needles in haystacks of molecules quickly and accurately.

MMLI is a partnership between the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Pennsylvania State University, and Rochester Institute of Technology. The institute fosters extensive collaborations among artificial intelligence (AI) and chemical and biological syntheses. Those collaborations serve to develop frontier AI tools and dynamic open-access databases. Current research at MMLI involves both small molecule discoveries and manufacturing.

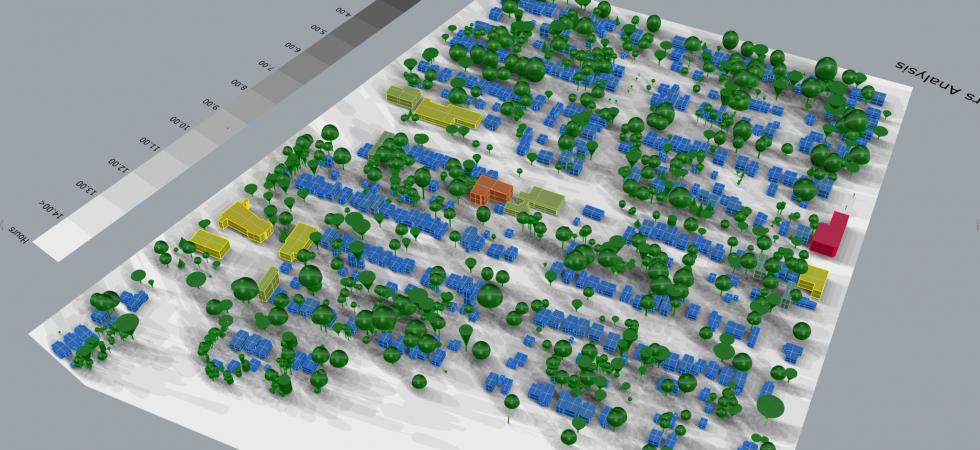

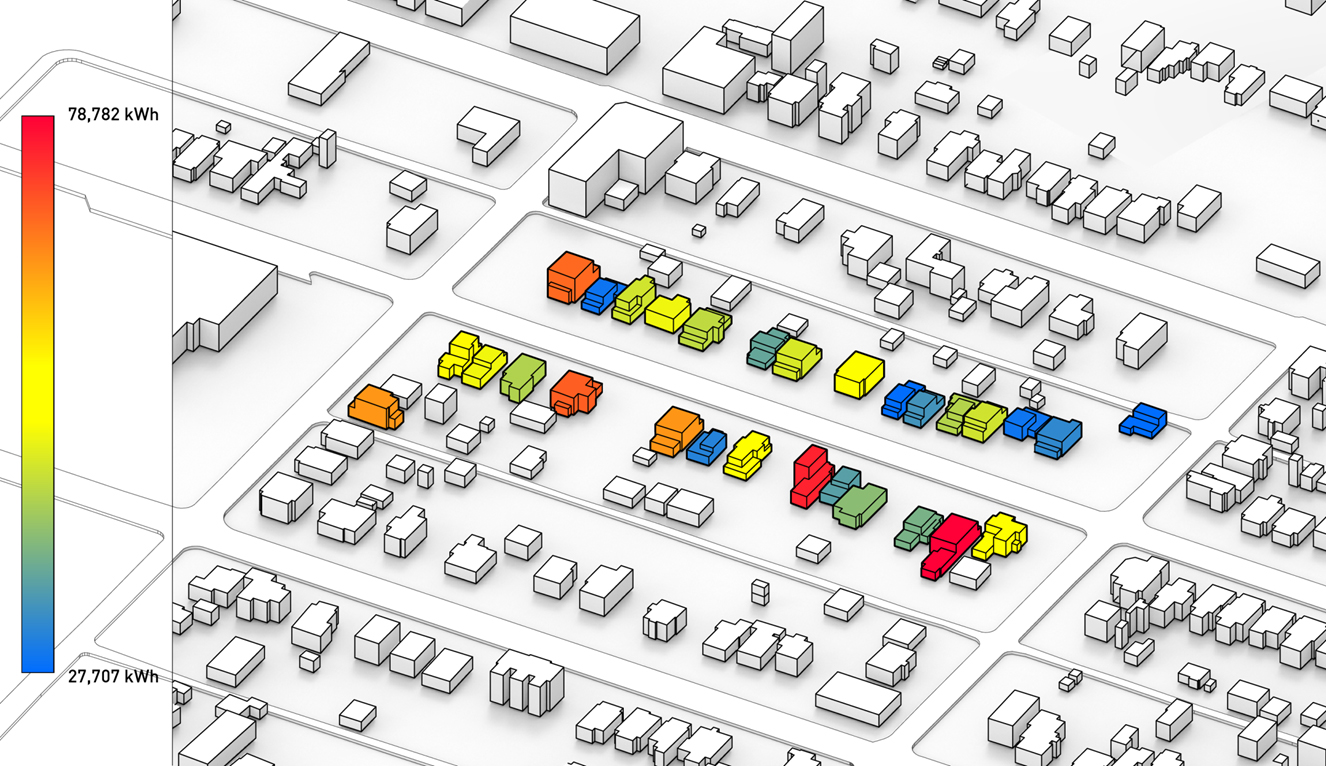

For molecule discoveries, the Institute is currently focusing on improving the performance of organic solar cells. Compared to silicon-based solar cells, the state-of-the-art materials for solar energy harvesting, organic solar cells, are more flexible. They can also be manufactured at large scales at relatively low prices.

However, certain caveats prevent organic solar cells from replacing silicon-based solar cells. Unlike silicon, organic molecules are less efficient at converting solar power into other forms of energy like electricity. Those molecules cannot endure sunlight irradiation for a long time. (Think of pigments on your outdoor furniture that gradually fade away under sunlight. That is sunlight irradiation degrading organic molecules on display.)

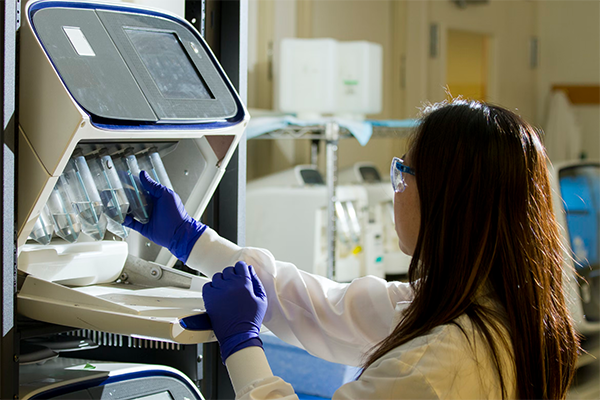

To overcome these challenges, MMLI is currently developing AI-enabled tools such as AlphaSynthesis to accelerate the discovery of long-lasting and more efficient organic molecules for sunlight harvesting. Guided by machine-learning models, the team led by Martin Burke is able to screen through potential candidates at high throughput. “The team has an ambitious ‘10-10’ target to create organic photovoltaics with a greater than 10% efficiency and a 10-year lifetime,” said Celine Young, Managing Director of MMLI. “Led by a team of experts in AI, automated chemical synthesis, and automated additive manufacturing, the MMLI is employing a closed design-build-test-learn loop to work towards this goal.”

In terms of chemical manufacturing, MMLI primarily focuses on catalyst discovery. Catalysts are a crucial component for efficient chemical production, as they lower the energy barriers of chemical reactions. A catalyst is a local guide who can always tell you the fastest route to a specific destination. Without an efficient catalyst, commercializing any chemicals beyond lab-scale syntheses would be a great challenge.

To find the best catalysts for certain chemical transformations, MMLI developed new AI algorithms to find catalysts that can assist in making the desired molecules. Currently, the team led by Scott Denmark is using AI-enabled tools in hard-to-find catalysts for carbon-hydrogen (C-H) bond oxidation reactions. These reactions can change the properties of a molecule. In C-H bond oxidation reactions, a catalyst breaks the C-H bonds in the molecule and facilitates the formation of new chemical bonds like carbon-oxygen (C-O) bonds. Those reactions are crucial in drug synthesis and converting feedstock chemicals into higher-value chemicals.

MMLI not only stands at the forefront of innovations in AI-based molecule syntheses, but the Institute also realizes the barriers entering the field of molecule synthesis and manufacturing. Broadly speaking, the field is only accessible to a handful of experienced specialists with years of training. To break down such barriers, MMLI created Thrust 5, which aims to train junior scientists, engineers, educators, and practitioners on advanced chemical synthesis and AI skills. They deliver “MMLI in a Box” to classrooms in the USA and launch the Molecule Maker Digital Learning Platform to expose K–12 students to molecule making early on in their education.

Get Involved

MMLI is currently seeking applicants for their MMLI Seed Grant Program. Find out more about this opportunity and submit your grant proposal here by April 30, 2022. The Institute is also seeking industry partners that foster knowledge sharing between the MMLI and industry researchers.

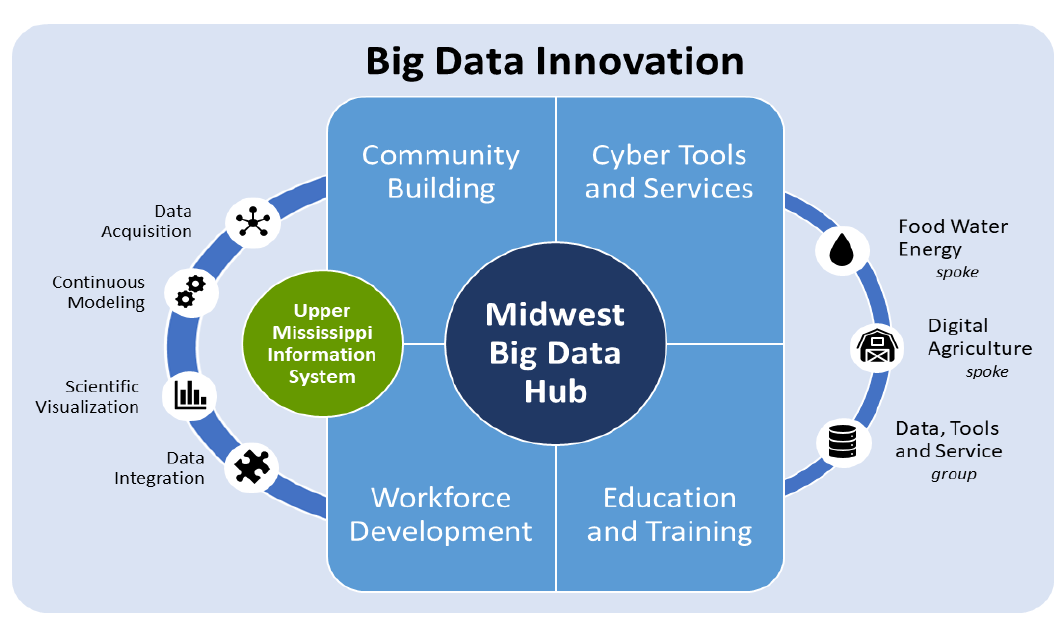

The Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub will be doing a community data needs assessment in the advanced materials space later this year to understand key challenges around materials data management. Contact us if you’re interested in participating, or if you’re aware of other people or projects we should profile here. The MBDH has a variety of ways to get involved with our community and activities.

The Midwest Big Data Innovation Hub is an NSF-funded partnership of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Indiana University, Iowa State University, the University of Michigan, the University of Minnesota, and the University of North Dakota, and is focused on developing collaborations in the 12-state Midwest region. Learn more about the national NSF Big Data Hubs community.